We have all heard the adage about what happens to you and me when we assume. Fair enough. However, assumptions will always exist; our brain makes them to quickly process information and build shortcuts to get us through the day, and we make them when designing and implementing strategies in our work.

We are investing time and resources into a particular program because we think that program is going to achieve the intended results, right? Why we think that program will lead to that result is based on a series of assumptions about what will happen once that program is implemented. So they are always there, underpinning our work and serving as the connective tissue in our strategy. We just don’t always talk about them. That’s where a theory of change comes in.

By technical definition, a theory of change (or TOC, as some people not-so-affectionately call it) is a conceptual roadmap that takes us from planned activities to anticipated outcomes.

The special sauce in a theory of change, though, (and what differentiates it from other tools that describe relationships between activities and outcomes) is that it tackles the how and why we expect the intervention to lead to the impact.

Through a careful assessment of the assumptions (conditions necessary for the program to be successful) that underpin why we expect these changes to occur, theories of change force us to be explicit about how things connect to one another. They require that we articulate those assumptions that sit below the surface.

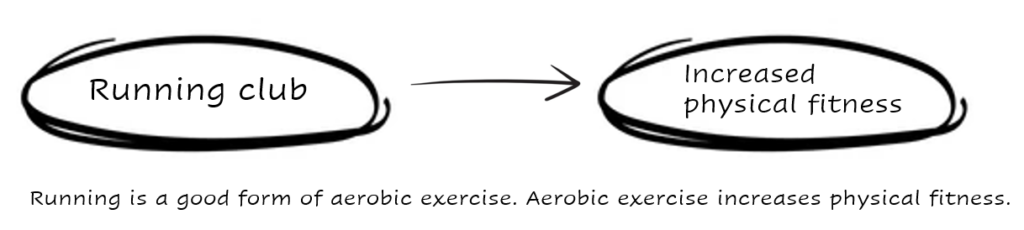

For example, I might expect that my afterschool running program for elementary school students will lead to increased physical fitness for the participants. That’s reasonable enough.

Why do we think this will happen, though? Is it because:

- Running is a good form of aerobic exercise and engaging children in aerobic exercise will increase their physical fitness?

- Reinforcing exercise with elementary school children will lead to other forms of exercise in their free time which will, in turn, increase their physical fitness?

- Running club will keep them from sedentary activities at home, and by virtue of not participating in those sedentary activities they will increase their physical fitness?

- Running produces endorphins, then endorphins create muscles, and muscles increase physical fitness?

- It just sounds like it should work?

Exploring those assumptions – ideally with my program team – accomplishes a few things:

- It provides a space for the team to reach common language about why we do the work we do.

- If we know why we are expecting something, we can identify what indicators we should see on the way to our goal. For example, if our work is based on the assumption that children will engage in additional exercise activity in their free time, we can track the extent to which they begin doing that. Then, we’d know if we’re on track for the longer-term goal.

- It creates an opportunity to check that our assumptions are reasonable. (That assumption about endorphins creating muscles, for example, is not rooted in science. If that’s the assumption underpinning our work, we might find that the strategy does not play out the way we expect).

So maybe the assumptions aren’t the issue; it is staying quiet about them that leaves space for confusion and disjointedness.

Do:

- Take the time to consider how and why you expect the outcomes from the activities you are undertaking.

Don’t:

- Assume (!!!) that everyone has the same understanding about your strategy. Make your assumptions explicit with your team and create space for them to articulate theirs, too.

+ Add a Comment

0 Comments